You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

24 February 2019

For fans of medieval European art, the Palazzo Madama is always a fun place to be, so, exhilirated by our visit to the Borgo Medievale down by the river, we're headed for the Museo civico d'arte antica, the City Museum of Ancient Art, at a brisk pace. Having lucked onto a parking spot a kilometre away to the west, we're hurrying past the Duomo, the Cathedral of San Giovanni, built in the 1490s on the site of an ancient Roman city gate and a succession of three earlier churches from the Lombard era. (Some of our photos of the interior, and the Shroud of Turin attractions, can be seen here.)

Alongside the Duomo and its belltower, that's the "New Wing" of the Palazzo Reale with its Sabauda Gallery, newly hosting several of the royal art collections of the family of Savoy that had been established as the Royal Gallery in 1832. The Gallery had several homes over the years until this wing of the Royal Palace, dating from the early 20th century apparently, was renovated to become the collections' final home and opened in December 2014 (we'd come to see it but arrived a week too early -- but we reappeared here promptly a year later). There's an archeological museum, too, in the basement.

We're dashing out onto the Piazza Castello and past the front entrance of the Royal Palace, the Palazzo Reale. The Savoy family and court gave free rein to a sort of overstated monumentalism, which pretty much defines the interiors here, and it is not one of our favorite palaces.

Now the Palazzo Madama, on the other hand, has character. It was originally part of Roman city defenses, then in the 14th century a castle of a cadet branch of the Savoy dynasty of the Haute-Savoie. It owes its present aspect to Marie Jeanne of Savoy-Nemours (1644-1724), Duchess of Savoy and mother of Victor Amadeus II of Savoy and later King of Sardinia, for whom she acted as regent from 1675 to 1684.

'The truth about Giulio Regeni' -- ubiquitous banners in Italy, recalling the Italian PhD student at Cambridge University who in February 2016 was tortured and murdered apparently by Egyptian security goons. Neither Egypt's nor Cambridge's explanations and denials seem ever to have made much sense, and Amnesty International has made these signs available all over the country.

Some kind of fun event is underway in front of the Palazzo.

The Piazza Castello with the Palazzo Reale at the far end. It's time to get started, but first . . .

. . . here's a view of the Palazzo Madama (and its shrouded entrance area) taken as we were leaving a few hours later. Duchess Marie Jeanne, upon being asked to retire from her son's politics in 1684, moved into the Palazzo Madama as it had been made more comfortable by a predecessor Duchess, Christine Marie of France -- eventually, however, she decided to commission a thorough do-over for what was still really the 15th century version of the ancient castle that had originally belonged to the Savoia-Acaja (or Achaia) cadet branch of the main Savoy line, which was merged into the main line in 1418.

The project was entrusted to the famous palace builder Filippo Juvarra, who worked on it from 1718 to 1721, after which it was left unfinished. What looks here like a substantial new structure is actually not much more than an elegant new façade, with entrance staircases and high-ceilinged rooms overlooking the piazza -- the rest of the castle has been tidied up but remains much as it was.

Like this (photo from December 2014) |

On the way to the ticket office

Since 1934 the Palazzo has been home to the so-called 'City Museum of Ancient Art' (Museo civico d'arte antica), though the really ancient art is in the Museum of Antiquities (Museo dell'Antichità) nowadays in the basement of the Sabauda Gallery wing of the Palazzo Reale. This one has 35 rooms on four floors, with medieval and Renaissance painting and sculptures, especially in wood, Baroque works above those, and on the top floor decorative works like ceramics, gold and silver things, period furniture and dress.

The Della Robbia look

A room full of wood carvings -- when we were here last, we had never heard of the Staffarda Abbey, but that's where all this stuff has come from. This is the Sala Staffarda, now housing the carved choir originally from the Cistercian Abbazia di Staffarda, just north of Saluzzo, brought here from the Casa del Vescovo when that was demolished in 1931.

This is the 'Antwerp Altarpiece', dated to about 1535 -- evidently when the Staffarda choir was dismantled at some point and moved to Pollenzo, the altarpiece was with it, but when the rest was moved on to the Royal Palace, the altarpiece ended up in a private collection; it was bought up by the Museum on the antiques market in 1998 and reunited with the rest of the choir. It is marked on the back with the warranty marks of the Guild of St Luke in Antwerp, a prestigious association of craftsmen in the Low Countries, and is said to be typical of altarpieces from Brussels and Antwerp that were in demand in the Piedmont in the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

The little dioramas apparently tell the stories of the marriage of the virgin, the nativity, circumcision, adoration of the magi, and so on.

We find no obvious reference to how, when, and why the Staffarda choir was dismantled and removed from the abbey, but there was a very destructive battle on the grounds of the abbey in August 1690 when the French army of Louis XIV decisively defeated Savoyard, Piedmontese, and Spanish forces and severely damaged the abbey buildings themselves. Perhaps there is some association there.

Late medieval hilarity

Somebody's in trouble

The nativity

It appears from the information panels that medieval religious sculpture flourished in the region of the Valle d'Aosta in large part because of the continuous flow of pilgrims trudging down the Via Francigena pilgrim route towards Rome. This Madonna and baby (by a 'Scultore piemontese-aostano') is dated to around 1270-1280.

The crowning of the Virgin, and scenes from the martyrdom of St Pantaleone, 1330-1340, from the Valpelline above Aosta city. St Pantaleon was remembered as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, in his case martyred in Nicomedia in the Diocletian persecution of 305.

These are meant to be scenes from the life of Mary Magdalene, attributed to the workshop of the Maestro della Madonna di Oropa (a sanctuary near Biella, northeast of Ivrea), dated to 1295-1300. It appears that the sculptor, like nearly everyone else then and now, has assumed that every non-Madonna female mentioned in the gospels must have been Mary Magdalene.

This is a 'paliotto' (evidently the front of an altar, or 'frontal') with Christ and the Virgin, and Saints Mary Magdalene, Peter, Pantaleon, Paul, and Catherine, by an unknown sculptor, dated 1240, and purchased in 1900 from the church of St Pantaleon in Courmayeur at the head of the Aosta Valley. (In 1897 the parish priest tried to sell it illegally, but it was impounded, and the sale to the Museum was brokered by Alfredo d'Andrade, the fellow behind the creation in 1882-1884 of the Borgo Medievale that we just visited a few hours ago.)

Another 'paliotto' with the Coronation of the Virgin and Saints Catherine, Griglia[?], Paul, Peter, Ursus of Aosta (an Irishman who died in Aosta), and Margaret.

Another anatomically-challenged Nursing Madonna on a polyptych, apparently from the late 14th century

The gentleman on the left is evidently St Martin of Tours with an allegorical figure representing poverty, by a Swabian sculptor, c.1500. The Madonna and baby is dated to about 1510.

The Death of the Virgin, attributed to Antoine de Lonhy, a 15th century itinerant painter, illuminator, and stained glassmaker who was active in the Piedmont region roughly 1470 to his death in 1490.

A confident and hopeful Enthroned Madonna and Infant Christ with an orb, by another Swabian 'active in Tyrol', ca. 1500 . . .

. . . by an unfortunate juxtaposition, another Madonna and Christ alongside it, less hope, less confidence, by a sculptor from the southern Piemonte, 1498

St Catherine of Alexandria, with two wheels, as if one hadn't been enough. By the Maestro of the Chapel of St Margherita at Crea (13km west of Casale Monferrato), late 15th century

The Lamentation of the Dead Christ, a classic piece, ca. 1480, by the Maestro of Santa Maria Maggiore (thought to be Domenico Merzagora from the Ossola valley)

A view of the layout

A classic St Michael with his 'dragon'. The Museum features a sizable number of works by a few individual artists, a good representative body of work for admiring each of them. One of those is Defendente Ferrari, a late 15th to early/mid 16th century painter who was born near Torino and was active throughout the Piemonte from at least about 1510 to 1535. The Museum refers to him as 'Il Gentile Maestro' and has quite a few of his works, especially polyptych panels and altarpieces, that were gathered by a 19th century fan and donated to the Museum in 1909.

This is St Michael the Archangel slaying the Satan dragon, dated to ca. 1530.

One of the cuter interpretations of Satan's appearance

This is Defendente Ferrari's Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, dated 1525-1530, with a very cute little Jesus.

We can never pass up pictures of the saint with the rocks on his head. That's St Stephen, the 'first martyr', shown with St Anthony of Padua, on one of the panels of a triptych by Gandolfino da Roreto, 1495-1500. Stephen the 'protomartyr' was mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles as having been stoned to death in Jerusalem, ca. AD 34-36, for having insulted the Jewish authorities, a foul deed witnessed by the Pharisee Saul before he graduated to become the late-arriving Apostle Paul.

A stunned St Catherine with her wheel and an affectless St Apollonia, holding one of her own teeth in the pincers; by Gaudenzio Ferrari, ca. 1471-1546, born in Vercelli and working in the Piemonte, a prolific contemporary of Defendente Ferrari but not related to him.

Just in the nick of time! The Sacrifice of Isaac, 1738, by Simon Troger from the Tyrol, made of ivory, walnut wood, gilded bronze, iron (for the sword), and glass (the eyes).

Time for a coffee in the coffee shop in Juvarra's North Veranda, with its huge arched windows

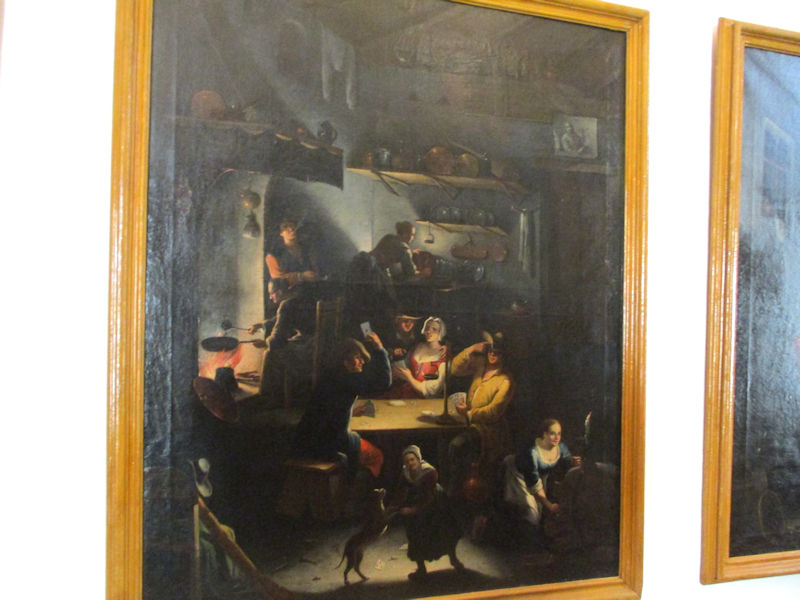

Another artist who like Defendente Ferrari is very well represented here is Giovanni Michele Graneri (1708-1762), a genre painter who was born and died in Torino. This picture is in fact labeled as Scene di Vita Torinese (1752).

This is apparently one of his best known pictures, The Punishment of the Sackers of Rotten Eggs, 1740.

Brueghel-ish village life: Winter Market

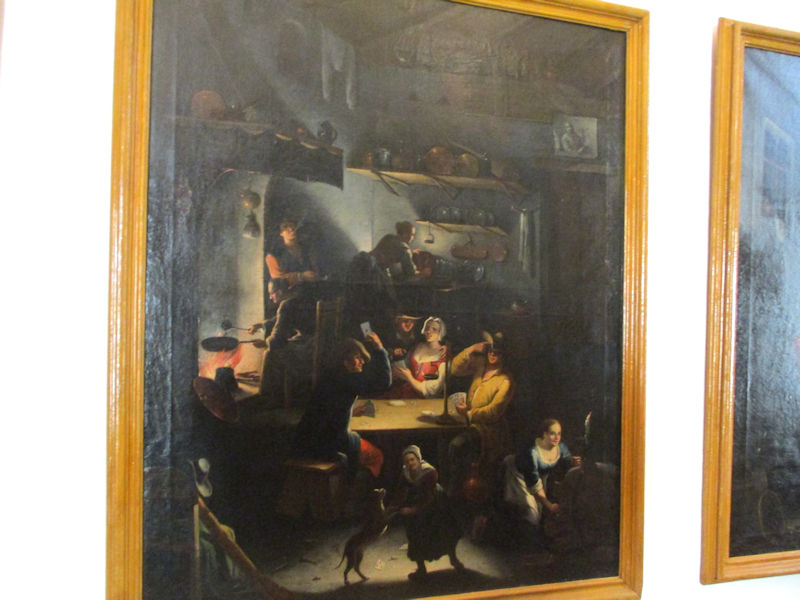

Graneri's The card players

A tavolino or small table with trompe-l'oeil stuff on it, by Pietro Piffetti of Torino (1701-1777), signed and dated 1758 on the title page of the book, a geography for children that was translated into Italian in 1738. The musical score shows excerpts of works by an oboeist in the Torino Royal Chapel.

Another corner room, great for viewing the city when the windows have been cleaned

The Piazza Castello from one of the clean windows

And the view to the west, down the tram lines on the Via Pietro Micca. The car's out there somewhere; maybe a bit more to the right, to the north. Maybe not.

Female saint with three-windowed tower: it's gotta be Saint Barbara, enameled terracotta, 1520-1525. Barbara is considered to be one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, martyred (according to the Golden Legend) under the Emperor Maximian in the late 3rd century. She had three windows (for the Trinity) put into the tower her pagan father had locked her up in; when he then beheaded her, he was struck by lightning and exploded, so she's also the patron saint of miners and artillerymen, anyone having to do with explosions. Her relics can be viewed in Kiev, Ukraine, as well as, since 2012, in Bloomington, Indiana.

Goodbye, Madama. We hope that we can come back someday.

A 15th century tower peeking out from behind the North Veranda in the afternoon sun

Past the Palazzo Reale -- the whole agglomeration of palaces, museums, and gardens here is collectively called the 'Polo Reale'. (The word 'polo', which is used in French as well -- e.g., the 'pôle relais zones humides' -- appears to be untranslatable.)

The Roman Gate, the Porta Palatina, 'one of the best preserved 1st-century BC Roman gateways in the world', though it's not known what palace was being referred to when it acquired its name.

Adjacent to the right is the expansive Parco Archeologico Torri Palatine and, across the street, the archeological museum in the Sabauda Gallery building.

The statues of Augustus and Julius Caesar are copies from 1934 but serve to invite tourists leaving the Polo Reale to come back again anytime.

A classy mall, empty on a Sunday

We're back on the road, and coming up on Agliè again (the Ducal Palace ahead of us is another part of the UNESCO World Heritage cultural property called 'Residences of the Royal House of Savoy' since 1997).

A farm

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website