Dwight Peck's personal website

Ten days in the Veneto (without Venice)

February - March 2017

You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

Padua: Chiesa degli Eremitani, Cappella degli Scrovegni, Musei Civici and Pinacoteca

Welcome to Padua (Padova), and the convenient parking garage at the north end of the old town, on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, 2 March 2017.

We're here to see particularly the Scrovegni Chapel and the picture collections in the Civic Museum, and it's just one block over from our carpark.

The Chiesa degli Eremitani (officially and ponderously, the Chiesa dei Santi Filippo e Giacomo agli Eremitani) is an Augustinian church begun in 1276 over an older structure similarly dedicated to Saints Philip and James. The two-part façade dates from 1360.

A typical Augustinian single nave, with in this case four small chapels along one wall and three more off the apse.

Just inside the front door, on either side, are the tombs of Ubaldino and Jacopo II da Carrara, both lords of Padua in the 14th century. Jacopo had succeeded in hosting Petrarch in the city for a time, and when he was assassinated in 1350 the poet contributed the verses shown on the plaque beneath the tomb.

The nave, in alternating courses of red and ochre brick

Damaged frescoes in one of the chapels, showing substitutions of missing parts

The Ovetari Chapel once boasted frescoes of St James by the young Mantegna, commissioned in 1448, along with some other artists of the Padua school -- the posters show what's now missing. Mostly, all of them.

On 11 March 1944, Anglo-American bombers left this behind them . . .

. . . and this is the Overtari Chapel today.

The Altar Chapel and presbytery, with a crucifix dated from 1370 . . .

. . . and some surviving scenes from the lives of Saints Augustine, James, and Philip by the Padovan Guariento di Arpo in 1368.

The elaborate tomb of the 16th century Padovan personality Marco Mantova Benavides, a humanist and jurist, editor of the works of Petrarch, and legal consultant to the Emperors Charles V and Ferdinand I and various popes.

The Church of the Eremitani, or Church of the Hermits, got its present short-name either because the Augustines were often referred to as the Hermit Friars or, more traditionally, because the adjacent cloisters provided guest accommodations for pilgrims passing through. The cloisters now house the Civic Museum, which we shall visit presently.

It's time to leave now.

One of the two cloisters adjacent to the Church of the Eremitani, with the entrance to the Scrovegni Chapel and the Museo Civico . . .

. . . all within the Arena Gardens, including the remains of the ancient Roman arena and associated artifacts.

The Cappella degli Scrovegni, or Scrovegni Chapel, is world famous chiefly thanks to Giotto, who was commissioned to do the frescoes, completed in 1305.

The Padovan banker Enrico Scrovegni purchased the land adjacent to the Roman arena in 1300 and got authorization to build his family chapel in about 1302 -- it was dedicated in 1305, by which time Giotto and his team had completed the amazing fresco cycles.

Take a break. Our group goes in in 10 minutes or so, and then we'll spend another 10-15 minutes in that modern anteroom watching an informative film whilst the indoor-outdoor climate equilibrates after the opening of the doors. It's an airlock, basically.

Patience will be rewarded. In early 1305, the Augustinian monks of the Eremitani sued Scrovegni because, though he'd been licensed to build a family chapel and burial place, he'd tried to turn it into a proper church, with belltower, thus cutting into the Eremitani's profits from the faithful. Evidently, the apse and transept had to be demolished, and that's why . . .

. . . the present apse is tiny. The walls and ceilings are covered with scenes from the life of Christ and of the Madonna.

The apse and choir

A cycle of scenes from the Life of Christ

The Last Supper. The Chapel was originally part of the Scrovegni Palace, which was demolished in 1827 to make room for some condos. In 1881 the city bought the chapel, knocked down the condos, and restored the Chapel. Thank you.

"Noli me tangere"

The rear wall with . . . The Last Judgment.

We love a Last Judgment, and normally skip over the parts about the virtuous souls being lofted happily into the heavens and then lined up in crowded ranks of angels, like a North Korean military parade, to sing the Lord's praises forever.

We tend to focus on the other part -- the Italian 14th century excelled in visions of the downside of the afterlife, especially after Dante's Inferno went into manuscript circulation.

It's not quite Bosch, but it's poignant anyway.

|

|

The Chapel also sports a full series of monochrome figures of Deadly Sins, in this case Envy and Wrath.

Our time's up. Let's keep it moving, thanks everyone; keep it moving please.

And now for the Civic Museum, over in the cloisters again.

The pinacoteca, medieval and modern

Poor young Agatha, with her martyr's palm and a plate with her iconographical credentials on it (Francesco di Simone da Santacroce, late 15th century)

Madonna and Child and some more martyred saints with their own iconographic identifiers -- Lucia (eyes on a plate) and Catherine of Alexandria (spikey wheel, and martyr's palm) (attributed to Boccaccio Boccaccino, early 16th century)

We collect beheadings -- this specimen is a Salome and the ex-John the Baptist by the Baroque artist Bernardo Strozzi of Genoa, a childhood Capuchin monk who, condemned by his superiors for his secular commissions, decided to leave the order in 1630 and got stuck in jail for it. He showed up in Venice a few years later, flourished, and died in there in 1644.

Childhood seems hardly worth it, in the rich kids' clothing styles captured by Chiara Varotari of Padua (she died in 1663 at the age of 78).

And it wasn't much more comfortable when you grew up.

A beautiful winter landscape by Bartolomeo Pedon, a late-Baroque painter working in Padua and Venice who specialized in variations of this picture.

One of our favorite Farneses, Ranuccio I, Duke of Parma, Piacenza and Castro after 1592, best known for his Great Justice in 1612 when he executed for rebellion the heads of nearly all the noble families in his territories, and became a thorough outcast of northern Italian polite society by publicly accusing all sorts of other great families, like the Gonzagas and Estes, of having been behind the plot. But he built the beautiful Farnese Theatre in Parma, so there's that.

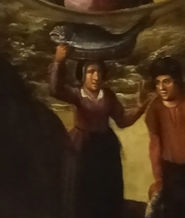

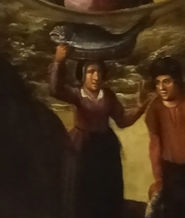

Christ preaching on the Sea of Galilee, featuring an unimpressed woman with a huge fish on her head, attributed to Adam Willaerts of Utrecht, 17th century

King Louis XIV, by a 'Pittore Francese', mid-17th century. L'État, c'est moi.

One of Giotto's crucifixes, this one dated to 1317

Christ descending to Limbo to fetch the pre-Christian righteous, by Jacopo Bellini, dated to about 1460, when he was living in Padua late in his life

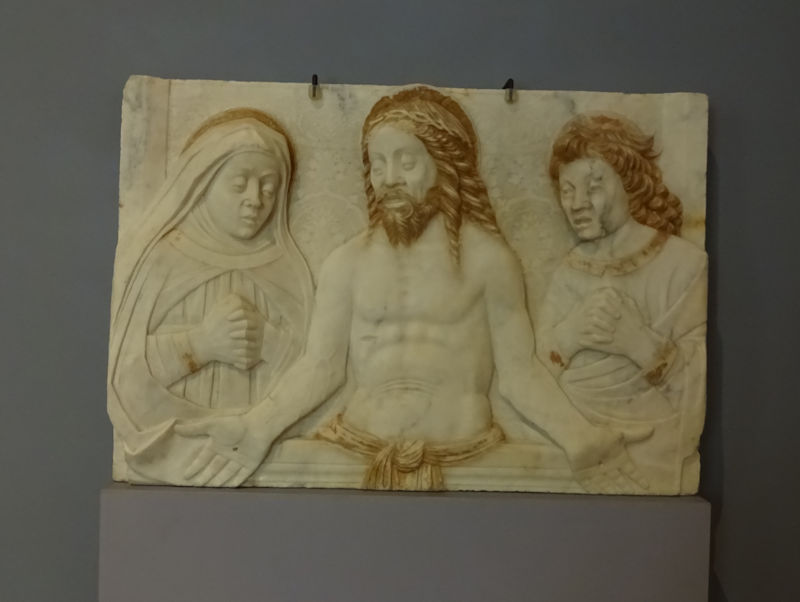

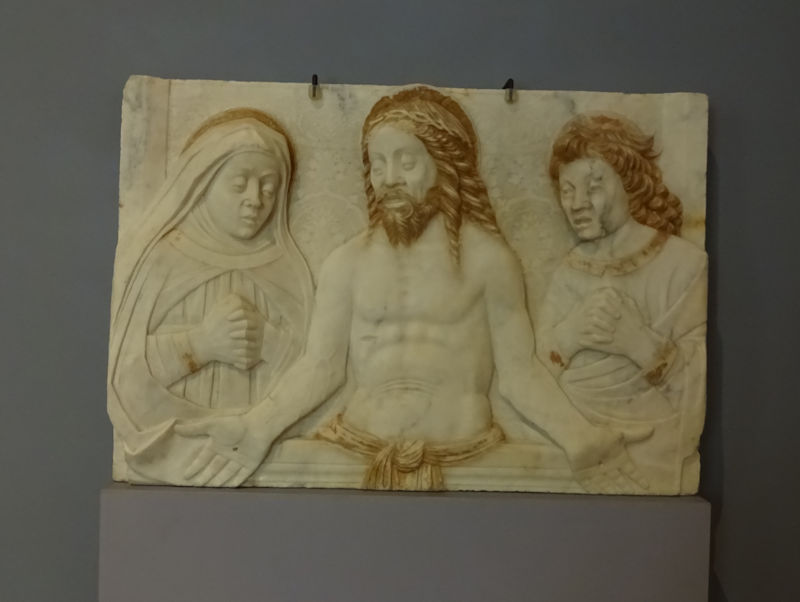

An odd pietà, late 15th century, by the workshop of Bartolomeo Bellano of Padua, who also worked with Donatello on Padua's Basilica di Sant'Antonio

A cute Madonna della Misericordia, sheltering the faithful and a kid who seems to have a noose round his neck, with saints, by an unknown Padovan painter in the mid- to late-15th century

Today's winner of the ugliest Madonna competition, with the runner-up in the ugliest Christ child category, early 16th century, attributed to a Pittore Veneto who didn't want his name mentioned.

The Archangel Michael slaying a dragon whilst babysitting, by the Venetian painter Lazzaro Bastiani, 15th century

A striking Mary Magdalene in extremis (with friends) by the fascinating sculptor in terra cotta Guido Mazzoni originally from Modena, late 15th century

A slow parade of biblical worthies

Nursing Madonna and Child with a stern collection of saints (Peter, Catherine, Lucia, and Paul) and two determined donors. And a disembodied hand grasping a key. Labeled as by Bernardino Luini (ca. 1480-1532).

St Rocco on the right, patron saint of victims of the plague (always contentedly calling attention to the buboes on his leg), dogs, and bachelors; by Sebastiano Florigerio, mid-16th century. Rocco, or St Roch, is often paired with St Sebastian (him of the arrows, which actually he survived, but was later clubbed to death), who was also a patron saint of the plague-stricken (and of archers).

Restorations in progress

We collect pictures of the Last Supper (this by Il Romanino, 16th century), chiefly to try to figure out what they were eating.

So what on earth is that?

Probably we will never know. (Frequently, especially in Spain, it appears to be a rat.)

The Martyrdom of Santa Giustina, or Saint Justina, by Veronese (1556). Justina of Padua, an additional patron saint of both Padua and Venice, was reputed to have been a royal princess and a disciple of St Peter the Apostle, as well as of the first Bishop of Padua, St Prosdocimus (who supposedly died ca. A.D. 100), and to have been martyred in A.D. 303.

Tintoretto's Dinner in the House of Simon the Pharisee (the collection also has a large Crucifixion scene by Tintoretto; a good picture, but a bad photo)

The museum layout

Annunciation to the Shepherds by Leandro Bassano (dal Ponte) of Bassano del Grappa, Jacopo Bassano's third son, late 16th or early 17th century

Judith with Holofernes' head (we collect beheadings, especially Judith, but also Salomé and Goliath), by Alessandro Tiarini, Lavinia Fontana's godson, 17th century

Il Tiranno, Ezzelino III da Romano, the allegedly monstrous lord of much of the March of Treviso including, at his peak, Verona, Vicenza and Padua in the shadow of Emperor Frederick II's attempts to dominate northern Italy in the years leading up to 1250. The sculptor, Giovanni Bonazza of Padua, was active in the late 17th and early 18th centuries and presumably made this likeness up out of whole cloth, or borrowed it from an earlier Attila the Hun.

A nicer work by Bonazza, a Mary Magdalene in a very non-biblical pose

To leave the collection on a more unsettling note, Faustino Bocchi specialized in often ribald pictures of imaginary dwarves, or nani, extremely popular in Bergamo and elsewhere in the early 18th century. Several are represented here, and in this one, a dwarf is saving his companions from a Giant Shrimp.

Now we're off for a visit downtown.

Next up: Padua walkabout

Feedback

and suggestions are welcome if positive, resented if negative, Feedback

and suggestions are welcome if positive, resented if negative,  .

All rights reserved, all wrongs avenged. Posted 8 June 2017. .

All rights reserved, all wrongs avenged. Posted 8 June 2017.

|