You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

The plan is to luxuriate for twelve days in Viterbo, with enthusiastic sight-seeing in the region, and a few days tacked onto either side of that for getting there and back.

Sightseeing in Viterbo (round one)

We're on the road from Calci back to the coast near Livorno, just south of Pisa, 25 November 2016.

Passing Montepescali on the E80 autostrada south

The pleasant autostrada franchise, Autogrill (motto, in English: "Feeling good on the move"). In this promotion, for every Perfect Menu sold, Autogrill and Coca-Cola will donate an equivalent package to the food-bank Banco Alimentare for the poor.

We're about to run out of autostrada near Grosseto and get dumped onto the horrendous old State Road following the Roman Via Aurelia, pothole by pothole along the coast.

In a blockheaded fit of GPS presumption, at Montalto di Castro the Volvo equivalent of Siri sent us up into scenic backroads inland, where at least we passed by impressive Tuscania.

Lovely countryside, but a hard way to make time to your destination

But at least our Volvo GPS got us correctly to the unaccountably free section of a large pay carpark just outside the medieval city walls that circle all round old Viterbo.

The city walls along the Via delle Fortezze parking lot, blessedly free of charge at the southern end of it

The San Pietro gate at the southern end of the walled city, leading into the medieval quarter San Pellegrino. Viterbo originated as an apparently not very important Etruscan town in the heart of old Etruria, about 50km north of Rome and not far south of the Lago di Bolsena; it was eventually assimilated into the Roman Republic like everything else in the region.

Not much seems to have been heard from Viterbo, or Vetus Urbs (the 'Old City'), during late Roman times, but in the dying days of the Lombard kingdom of Italy, King Desiderius is said to have fortified Viterbo in AD 773 to put pressure on the papacy in Rome (and promote his own antipope). Charlemagne routed him out of the Lombard capital in Pavia in 774 and sent him into exile in Corbie Abbey in northern France.

Scurrying along the Via San Pietro into the San Pellegrino quarter (not scurrying really; dragging two huge suitcases over the cobblestones). With the 8th century Frankish interventions, Viterbo was included among the territories of "St Peter's Patrimony", i.e., territories owned by the Church, i.e., the Papal States, though by the late 11th century its internal governance was that of a free commune like other towns at the time.

We're just letting one of the suitcases rest for a moment along the Via S. Pellegrino, alongside the Chiesa di San Pellegrino on the left and the Palazzo degli Alessandri ahead.

The Piazza San Pellegrino, with the San Pellegrino church, whacked by Allied bombs for some reason in 1944 but largely repaired. The factional violence of the great families of Rome, and agitations of Arnold of Brescia and the short-lived Commune of Rome, made the popes and their friends consistently uncomfortable, and by the time of Eugenius III, who fled to Viterbo in 1145, the city was becoming a welcome place of papal refuge in troubled times (he was besieged here, but unsuccessfully).

The Via San Pellegrino main street proceeds happily through some interesting urban features. A few years later, in the 1160s, the Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa, eager to reassert his Hohenstaufen imperial rights in Italy during his 3rd and 4th Italian campaigns, established his favorite antipope, Paschal III, in Viterbo.

Here we are, across from the tiny Via delle Caiole. We're told that in the late 12th century Viterbo may have been at the height of its prosperity, with a population of as many as 60,000 souls (which sounds unlikely; the population in 2011 was 64,000).

Our front door

The Casa Vacanze La Suite del Borgo -- Stefano and Daniela have four fully renovated flats in a small area in the centre of the San Pellegrino quarter, very comfortable, charming, and very inexpensive. Our hosts are extremely friendly and helpful, extremely cat-friendly as well, and Stefano speaks fluent English.

Squirrel is not yet secure in her new surroundings.

The living room and kitchen (mind your head). We're in the Suite Verda, on the third floor of an 11th century building, just along from our hosts' HQ, with the larger Suite Viola (to which we'll be moving next week when our friend joins us) and the Suites Blu and Arancio nearby.

Kristin and Squirrel settling in

The bathroom (mind your head; really, mind your head)

The view out the living room window

The Via San Pellegrino. With small clubs along the street on either side, on a few nights a week the street itself joins the club scene.

Back downstairs for a first day's sightseeing orientation session, 26 November 2016

The tiny Via delle Caiole across the street

-- Which way shall we go?

The Piazza San Carluccio, and the 'Ballet Dream' dance school. Viterbo is preparing for its first Christmas market and festival, to begin next week, and stands are being built in many parts of town.

Like here.

The Piazza delle Morte, on the way towards the cathedral. The piazza, and its fountain, date from the mid-1200s, but the name comes from the occupants of a nearby sacred building of the 'Brotherhood of Prayer and Death'. It looks pleasant enough now.

Across a bridge, the Ponte del Duomo, with a bustling thoroughfare underneath, that's the Palazzo Farnese. Dating from at least 1278, it came into the Farnese family in the mid-15th century and is said to have been a childhood home of Alessandro Farnese, later Pope Paul III (1534-1549), and his beautiful sister Giulia, mistress of the Borgia Pope Alexander VI in the 1490s.

The Duomo di Viterbo or Cattedrale di San Lorenzo . . .

. . . and its Gothic belltower from the mid-14th century, with its Sienese- or Tuscan-style alternating stripes on the upper half.

The Cathedral of San Lorenzo (or St Lawrence), built at the high point in the medieval town, the centre of the Etruscan settlement, and apparently over a Roman temple to Hercules -- it was consecrated in 1192 but significantly altered in the 16th, and again in the 17th and 18th centuries; following the devastating Allied bombing of May 1944, it was restored in a more Romanesque "neo-medieval" style, with many of the baroque accretions removed.

The Casa Pagnotta, evidently from the 13th century, named for the churchman who bought it in 1458, now a museum bookshop -- it was massively damaged by the Allies but restored to original specifications.

A fine, narrow nave with two aisles, with two rows of columns supporting 12th century arches which survived the Allies' war efforts

Just inside the door, a baptismal font by Francesco da Ancona (1470) on an earlier pedestal.

The nave with some severe war damage at the apse-end of it, and its original Cosmati-style floor

The chapel of Saints Ilario and Valentino

The spartan presbytery (with allegedly a small door at the back leading into a hidden Chorus of the Canons from the 16th century)

A 16th century lockable tabernacle set into the wall, normally to store elements of the Eucharist, marked with "sacra olea"

We're on the porch of the Cathedral above the Piazza di San Lorenzo (filled with half-completed Christmas market stalls) and facing the main staircase and loggia of the Papal Palace.

In 1257, in frantic flight from the insecurities of life in Rome, the Pope and the Papal Curia transferred to Viterbo -- the existing bishop's palace was enlarged to become suitable for the papal administration, which remained in residence here, with a few short breaks, until 1281 (when it moved on to Orvieto, then Perugia, and then to Avignon in France). The present Palazzo dei Papi, connected to the Cathedral, was completed in about 1266.

The loggia, with delicate double-columns

The 15th century fountain, sporting the arms of the prominent Viterbesi Gatti family (Raniero Gatti, Captain of the People at the time, had commissioned the building of the Papal Palace two centuries earlier)

Carparks in the centre of the old city, seen from the Palazzo dei Papi. It was the Pope Alexander IV who removed the Curia to this place in 1257, to be succeeded by Pope Urban IV (back from the Crusades) and Clement IV, then to be followed by the Visconti Pope Gregory X, who was elected here in the world's longest papal election, 1268-1271 (the townspeople were so fed up that they locked the cardinals in and allowed only bread and water to be sent in until a result was announced), and then in 1276 by the six-months Pope, Innocent V, and by the two-months Pope, Adrian V, and then . . .

. . . by the eight-months Pope John XXI, the only Portuguese pope, a famous logician and physician, who was elected in 1276 and crushed to death in May 1277 when his study in this new palace collapsed on him.

The zoom view from the Papal Palace: the mid-18th century Church of the Trinità across the way. The Orsini Pope Nicholas III was elected next after poor John XXI, a five months' election process this time, with three of the cardinals partisans of the Frenchman Charles of Anjou, newly King of Naples and Sicily, and three favoring an Italian. Nicholas died in August 1280, and the Angevin cardinals had nearly enough votes to elect one of their own, but not quite; after another long stalemate, in February 1281 a mob from the city broke into the Papal Palace and kidnapped two of the cardinals, and the pro-French party was able to elect a Frenchman as the new Pope with the name Martin IV.

The Viterbo government weren't having it, so Martin IV couldn't be crowned as pope here (especially as the city had been excommunicated for kidnapping the cardinals), and Rome wouldn't allow him in, so he removed the Papal Curia to Orvieto for his coronation; but then they threw him out as well, and the entire Papal Curia moved to Perugia in 1284, where Martin died a few months later after becoming ill at lunch (Dante, in the Purgatorio, implies that his fondness for eels from Lake Bolsena had something to do with it). (There are so many funny papal stories.)

How do they get water up to the fountain here on the balcony?

That's how.

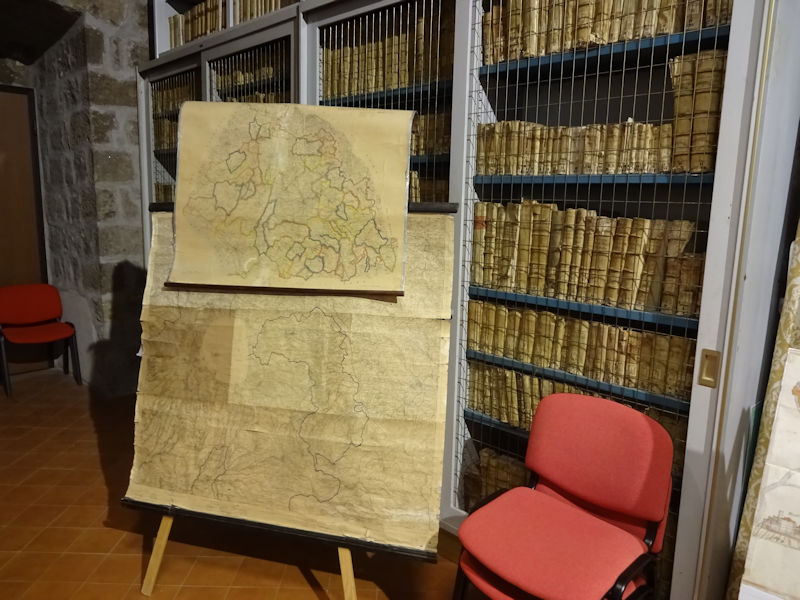

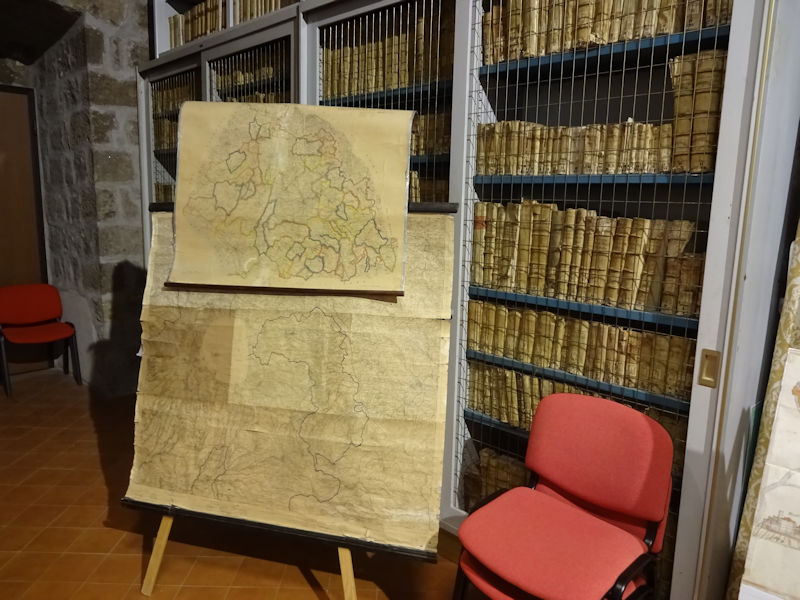

The Diocesan library

Not much else is open in the Papal Palace, except perhaps on special occasions. We asked a local what's up with that, and she said that the Bishop doesn't really want a lot of people around.

The 13th century fountain in the Piazza delle Morte

We're strolling southward down the hill to the Parco del Paradosso (we dined at the Ristorante Il Paradosso one evening; it was a disaster).

From the Parco del Paradosso, looking back up at the Duomo

The San Pellegrino quarter, as we're progressing up the Via delle Caprarecce on the far side of the park

The Chiesa di S. Andrea, St Andrew, with a three-arched portico in front, built in the late 12th century when this neighborhood was being laid out and attested in documents in 1236. It fell nearly into ruin by the 19th century but was restored in 1902; all to naught, as the Allies bombed it to smithereens, and it's been reconstructed to its early Romanesque glory, but minus most of the original frescoes. It was closed in any case, and we didn't get in.

"Our gate", the Porta San Pietro, protected by its small adjoining castle

The Porta Romana train station outside the walls, with an animated discussion going on between the rail lines

Back into the old town, in the Piazza Fontana Grande, this is the Fontana Grande -- begun in 1212 and completed in 1279 during a well-planned expansion of the city and of its public services.

The view from the Fontana Grande up Saffi Street past a civic tower

Chips Land (Amsterdam)

Down by the parking lot del Sacrario, presently occupied by a street market, this is the former Chiesa di S. Giovanni Battista degli Almadiani, funded by Mr Almadiani for the Carmelite order in 1510, now apparently an educational science exhibition venue, the Sala degli Almadiani.

From the Piazza del Plebiscito, that's a view back down the road to the Sala degli Almadiani and the street market, with the octagonal monument now dedicated to the fallen army aviators, apparently built in 1494 in gratitude by those who escaped the plague.

The administrative centre, the Piazza del Plebiscito, and the administrative buildings in the Palazzo dei Priori (or First Citizens), otherwise the 'Palazzo Comunale' or city hall. The piazza was cleared of a pre-existing cemetery in 1264 in preparation for the removal of the Papal Curia to Viterbo -- evidently the palazzo too was begun in 1264 with the upper stories added in 1460. The building on the left, formerly the Palace of the Captain of the People, rebuilt in 1771, is now the Palazzo della Prefettura, or police headquarters, into which I mistakenly wandered on my sightseeing rounds and was politely sent on my way.

Along the north side of the piazza, this is the Palace of the Podestà, or chief administrative officer, also built in 1264, now housing administrative offices and a few commercial establishments, connected to the Palazzo Comunale through the city's art museum. The clock tower, now just called the Torre dell'Orologio, was rebuilt in 1487 replacing an earlier tower that had already had a public clock since 1424.

The lion and the palm affixed to the clock tower are the symbols of Viterbo, the lion for the Guelph faction and the palm as a memorial to Ferento, a nearby rival town that was conquered and absorbed into the city in 1172.

The fourth side of the piazza is partially taken up by the otherwise uninteresting Church of St. Angelo in Spatha; consecrated in 1145, it was bombed out in 1944, but has been made functional again.

Outside the Church of St. Angelo in Spatha, however, there is this interesting Roman sarcophagus, a lion killing a wild boar in a hunt, evidently commemorating the Bella Galiana, from a legendary tale. It's signed, though, "L. Funari, 1998" (it's a worthy copy; we subsequently found the original, showing the ravages of time, safely stored away in the Museo Civico).

It's time for a little restorative something in the Caffè Centrale in the Palace of the Podestà.

There's a poorly attended book market going on outside the Palazzo Comunale.

The courtyard of the Palazzo Comunale

A fountain in the open courtyard of the Palazzo Comunale

And the view across the way -- the church of the Trinità again

The Fountain of Lions in the Piazza delle Erbe, just up the Via Roma from the Piazza del Plebiscito

The day is waning, thoughts turn to dinner. Kristin has a recommendation to pursue. In the Via della Marrocca.

It's not well marked; in fact, it's scarcely marked at all, but . . .

. . . we'll make our reservation for this evening, Il Richiastro (apparently a dialect word for a courtyard), and we weren't disappointed.

Tomorrow: an excursion into Rome.