You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

It's an hour's drive from Gubbio northward on the SP3 towards Fano on the Adriatic, turning off on the little SS73bis to Urbino.

We've parked in a little carpark at the south end of the city, 18 November 2015, and -- no elevators up into town this time. This is the Via Aurelio Saffi, which appears to be in the university district, though throughout the centro storico nearly everything seems to be in the university district.

Along the Via Saffi to the Piazza Rinascimento, we're passing the walls of the Ducal Palace on the left with the Duomo just ahead. "Historic Centre of Urbino" was accepted as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1998.

The obelisk is said to be one of a pair brought to Rome from Sais in Egypt in AD 90 for use in the Temple of Isis in the Campus Martius; when it fell over and broke into pieces, it was donated to Urbino by papal authorities and reassembled here in 1737.

There was a small town here in Roman times (hence the name: a little urbs), but it was sufficiently important by the 6th century that the Byzantine general Belisarius took the trouble to capture it from the Ostrogoths, after a three-year siege, in AD 538.

The present Duomo, the Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta di Urbino, is a neoclassical edifice completed in about 1804 following the collapse of the previous cathedral in an earthquake in 1789. The previous building dated from the early 11th century but had been thoroughly remodeled by the Montefeltros in the late 15th. To its left, behind the traffic chain, is a rear external courtyard of the Palazzo Ducale.

Urbino's pride-and-joy is the Ducal Palace, built by the famous Federico III da Montefeltro, the 2nd Duke of Urbino, which (since 1912) also houses the National Gallery of the Marches region.

The famous courtyard (copied on a smaller scale by the Duke's palace in Gubbio). We've come in the back door, as it were; the splendid two-towered façade faces out towards the countryside to the west of the city, and we only got a glimpse of it from the fortress on a nearby hill.

After centuries of domination by church authorities and feudal families, Urbino became a self-governing commune for a time, but from about 1200 onward it came under the powerful influence of the Montefeltro family, named for the mountainous region of the Marche and San Marino just to the north of Urbino. Buonconte I was named Count of Urbino by the Emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen ('Stupor Mundi') in 1226, and though the city passed in and out of papal control over two centuries (most notably under the Cardinal Albornoz's papal campaigns in 1355 and afterward), the persistently-Ghibelline (pro-Imperial) Montefeltro family, with control of the entire surrounding region, were nearly always able to hold sway over Urbino, either by force or at the least by getting themselves elected podestà.

The apogee of Urbino's fortunes and its Renaissance reputation came during the tenure of Federico da Montefeltro, who initiated the building of the palace over the pre-existing "Palace of the Jole". We looked into the career of Federico a little bit the other day when visiting his palace in his birthplace city of Gubbio:

"The Duke in question is Federico III da Montefeltro (1422-1482), lord of Urbino after 1444 and its Duke after 1474. He was born in Gubbio as the illegitimate son of the then lord of Urbino and Duke of Spoleto, and rose to become one of the most successful soldiers of the age, as well as one of its most revered patrons of Renaissance art and culture, called 'the Light of Italy'."

The arms of Duke Federico. His motto, engraved everywhere, inside and outside of his buildings, seems to have been "FE DUX", presumably 'Federico the Duke'.

"Federico began his career as a condottiere or mercenary commander at 16 under Niccolò Piccinino, and when his half-brother the first Duke of Urbino was assassinated in 1444 he seized that city for himself. He sometimes paused but never ceased his military career, leading his company under Francesco Sforza, then in the service of Florence, then of Milan in 1450 after Sforza had become Duke there -- then of the Aragonese King of Naples against Florence, then for the Pope in the Kingdom of Naples, and in the Marche against his lifelong enemies the Malatestas; then for Milan again under Galeazzo Sforza, and then in 1469 he was sent by the Pope to occupy Rimini but decided to keep it and defeated a papal army to do so, though he then sold it back to the Malatestas. Eventful life."

The great hall of the Palace of the Jole

"The next Pope, a della Rovere, re-created him Duke of Urbino in 1474, married his own nephew to Federico's daughter Giovanna, and sent him off to subdue the Florentines; he brought 600 troops to await the success of the Pazzi Conspiracy against the Medicis in 1478, but it didn't succeed and evidently he went home. In 1482 he was hired by Ercole I of Ferrara to attack Venice, but died of a fever on the way."

That naked person on the right, in fact, is Jole, properly Iole, who was beloved by Hercules/Herakles (left) and unwittingly the occasion of his death by poisoned cloak by his jealous wife Deianira.

Federico was succeeded in the dukedom by his son Guidobaldo (portrait below), but in 1502 Cesare Borgia, with financing by his father Pope Alexander VI, captured the city, but when Cesare's campaign collapsed with his dad's death in the next year Guidobaldo was able to reclaim his title. The Duke had no heirs of his own, however, and had taken his sister's husband Francesco Maria I della Rovere as his heir, so that when he died Della Rovere, with the help of his uncle Pope Julius II, was able to succeed to the dukedom.

The reign of Francesco Maria I, another formidable mercenary commander with a long career, as Duke of Urbino was interrupted only once, when the Medici Pope Leo X excommunicated him in 1516 and gave the dukedom to his own nephew, Lorenzo II de' Medici, but Lorenzo died in 1519 and Francesco Maria was able to return after Pope Leo's death in 1521. He died in 1538 and the dukedom remained in the Della Rovere family until it was finally absorbed into the Papal States in 1626.

An altarpiece, one of many in this collection, this one by Antonio Alberti da Ferrara in the early/mid 15th century.

We collect beheadings, and this one of David and Goliath by Orazio Gentileschi, in the late 16th century, is embarrassingly tame compared to the best beheading of them all, the Judith and Holofernes by his daughter Artemisia.

Another very laid-back Goliath beheading, this by another favorite, Guido Reni, probably early 17th century. Beheading almost as an afterthought.

We also collect pictures of Madonna and Child Enthroned with anatomically incorrect nursing in progress (Pseudo Jacopino di Francesca, early 14th century)

And we also collect pictures of the Last Supper, mainly to confirm our suspicion that what the Disciples are shown to be having for dinner is most often a rat . . .

. . . as apparently they are in this case, too (the top right panel of an altarpiece by Giovanni Baronzio da Rimini, early/mid 14th century).

And moreover, we also collect pictures of Mary Magdalene, to count how many times she's shown as the pious best friend of Jesus and how many, on the contrary, as the fiercely penitent former prostitute, usually pictured with full-length blonde hair both to indicate prostituteness and to cover habitual nakedness. This by Bartolomeo di Tommaso, mid-15th century, shows the Maddalena as a Fallen Woman Newly Pious and an excessively strange John the Baptist.

This, called the Madonna di Senigallia, was created by Piero della Francesca in 1474; the artist lived at the court of Duke Federico and his son from 1469 to 1486.

This strangely geometrical Flagellation of Christ, Piero della Francesca, 1455-1460, has for centuries kept viewers paying more attention to the identities of the three worthies in the foreground than to the oddly perfunctory flagellation.

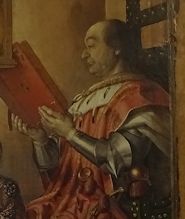

Federico III, the 2nd Duke, shown from his "good side" (since he was disfigured by jousting wounds on the other) and his son and successor Guidobaldo. This is often attributed to the Spaniard Pedro Berruguete, about 1476, but to Justus van Gent [Ghent], also called van Wassenhove, as well, as he was also one of the Duke's court painters at that time. [Round his left knee the Duke is wearing the English Order of the Garter, bestowed upon him by King Edward IV.]

The Duke's famous 'studiolo', his little study wherein he could study, contemplate, meditate, get away from the madding crowds, and also entertain and impress his many illustrious guests, some of whom are pictured amongst those here.

The wood inlay technique of marquetry, called intarsia, was very popular in northern Italy in the 15th and 16th centuries. These are intact, but in his studiolo in the Ducal Palace in Gubbio there is only a brilliantly executed modern replica, for the original roomful was sold off in 1874 and ended up in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Portraits of worthy historical figures and contemporaries, many of them now missing. The Duke's collections of books and art were said to have been prodigious, and the additions in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche make the Palazzo Ducale a pinacoteca well worth visiting. But it need not have turned out so, because much of the Duke's own collections were looted in the tumultuous times after his death. Many of his pieces, including furniture, passed with the dowry of the last della Rovere heiress, who married Ferdinand II de' Medici, to become the core of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, and most of his famous library was incorporated into the Vatican Library in 1657. Napoleon's French, who occupied the city from 1797 to 1800, carried off a lot more to form the core collections of the Louvre in Paris and the Brera in Milan.

In addition to the artists shown above in my hasty 'No Flash' photos, the present collection includes works by Paolo Uccello, Titian, Luca Signorelli, and Timoteo Viti, and Raphael Sanzio grew up here as his father Giovanni was one of the Duke's court painters (and wrote an epic poem about Duke Federico's life).

That's Duke Federico on the left, holding what could be mistaken for a pool cue. While Raphael was visiting the court here over the years, he became close friends with Baldassare Castiglione (and painted the famous portrait of him now in the Louvre). A relative and client of the Gonzagas of Mantova, Castiglione served as an active diplomat for the Gonzagas, and when in 1504 he met Guidobaldo, Federico's successor, on mission in Rome, he was invited to take up residence in the court of Urbino. Guidobaldo's wife was the elegant and highly cultured Elisabetta Gonzaga, who inspired much of Castiglione's poetry and plays often for court performance -- the visitors to Urbino in her lifetime, during her marriage and then as regent for her adopted nephew Francesco Maria della Rovere, included some of the most illustrious figures of the era (hounded by the Medici papacy, she died in poverty in Ferrara in 1526).

Castiglione later re-entered the diplomatic service of Mantova and by 1524 had been appointed by the Pope as Apostolic Nuncio to the court of Emperor Charles V in Madrid (the Pope blamed him for failing to send warning of Charles V's Sack of Rome in 1527, but eventually apologized for that). He died in Toledo, Spain, of the plague in 1529.

In 1528, Castiglione published in Venice what may have been the most important book in Europe in the 16th century, Il Cortegiano, a book-length dialogue led by Elisabetta Gonzaga set at the court of Urbino in 1507 -- it brilliantly outlines the upbringing, character, and etiquette of the "perfect courtier" and ideal Renaissance gentleman, and provided a model that was adopted sometimes slavishly in courts all over Europe. The translation into English by the English diplomat Sir Thomas Hoby, The Book of the Courtier (1561), was influential beyond estimation in forming the values and aspirations of the upper classes in Elizabethan England.

Kristin admiring The Communion of the Apostles, an okay picture by Justus van Gent (Giusto di Gand, aka Joos van Wassenhove).

A roomful of tapestries, and FE DUX inscribed across the fireplace

A Mary Magdalene looking more pious than prostitutish, by Timoteo Viti, early 16th century

Raphael's Santa Caterina (of Alexandria; she's standing on her spiked wheel)

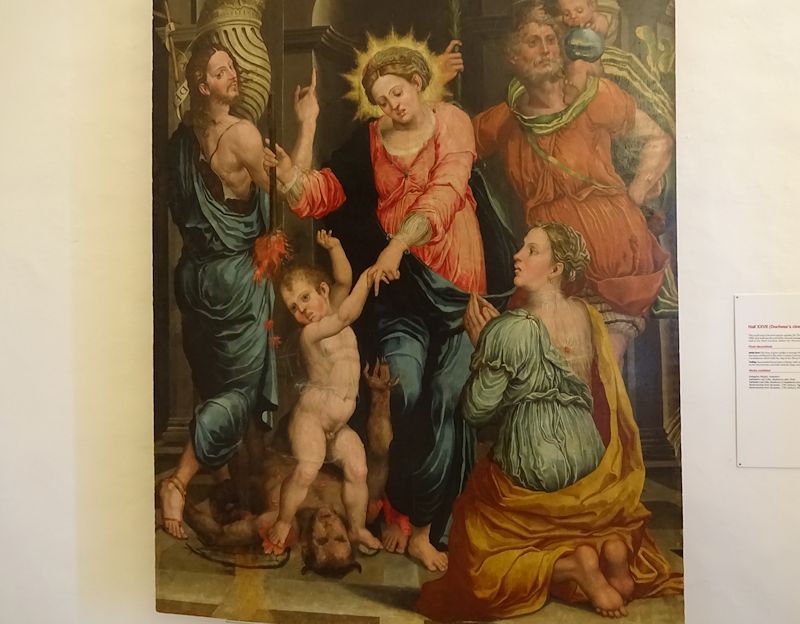

The Baby Jesus stomping the daylights out of the Evildoers

One of three paintings of similar purpose (the others are in Baltimore and Berlin), the "Ideal City" (ca.1480s) is often used to illustrate Renaissance values of mathematics, perspective, and city planning -- it has been attributed to Piero della Francesco, to any one of the artist/architects associated with the building of the Ducal Palace, Fra' Carnevale, Luciano Laurana, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, and Donato Bramante, and even to Leon Battista Alberti. The attribution here is tentatively made to Luciano Laurana, but Roderick Conway Morris in the New York Times, reviewing a 2012 exhibition on this subject in Urbino, writes that "Central Italian Painter" was preferred there.

An intarsia door, ordered up by Duke Federico after he saw similar work in Florence in 1472, shows a similar interest in urban perspective.

The Last Supper: so what's for dinner? (said to be by Andrea Boscoli, late 16th century)

If he could feed 5,000 with five loaves of bread, twelve disciples can probably make do with one . . . is it a rabbit?

Back to the external courtyard, and peckish

Kristin's found a splendid little restaurant and may be impatient.

The Neoclassical façade of the cathedral was reconstructed after the earthquake of 1789 (Urbino sits on the Earthquake Central fault line), consecrated in 1809. There's not much to see, except for the tomb of Polydore Vergil, the brilliant humanist scholar who was born here in Urbino but emigrated to the court of Henry VII in England in 1502, in his early thirties, and whilst enjoying church appointments there wrote a number of significant books -- most importantly, the Anglica Historia (1513, with a final edition in 1555), or history of England, which influenced many subsequent authors and through them to Shakespeare. He returned to Urbino at the end of his life and died here in 1555.

The Corso Garibaldi northward downhill from the Duomo. Lots of students around, having fun, pondering their futures.

The Piazza della Repubblica, more or less the city centre. Urbino suffered surprisingly little bombing during World War II, by agreement between the Allies and the Germans to respect a red cross painted on the roof of the Palazzo Ducale. Near the end, the Germans tried to blow up the fortifications, but local workers employed by the German army sabotaged the charges. The city was liberated in August 1944 by Polish and English troops, aided by local partisans.

The portico of the Chiesa di San Francesco, going uphill on the Via Raffaelo Sanzio

The 14th century church of San Francesco . . .

. . . renovated in the 18th century

The belltower of the Chiesa di San Francesco

Straight uphill again

Street scene, Urbino

We're looking for a Sony camera battery, not so easy to find, and we've been directed to some likely possibilities outside the city walls, near the Porta Santa Lucia at the northeast end of town.

We discover a large piazza and an attractive elevator

The view of the countryside looking north

The shopping centre -- 10 floors of shops and parking, but no Sony camera battery. Oh well.

Back inside the city walls, we're wending uphill into another university district

The belltower of the Chiesa di San Francesco from the 'Belvedere Piero della Francesca'

The Franciscan Church of San Bernardino, a few kilometres away, built by order of Duke Federico in 1482-91 as a family mausoleum, with help from Donato Bramante. Both Federico and his son Guidobaldo are still in there.

Downtown vista

On a hilltop just north of the city centre, the Parco della Resistenza and the Fortress Albornoz. According to the Urbino website, the fortress was not built by the papal fixer Albornoz himself, but by his immediate successor as papal legate for the recalcitrant papal properties, the French Cardinal Angelico Grimoard, brother of Pope Urban V, between 1367 and 1371.

It's not a very interesting fortress from the outside, and there was no getting into it, at least not today. The obvious purpose of the installation, built over demolished Montefeltro properties, was to intimidate the population, but the Montefeltro family had reasserted its influence in the city by 1375.

The view of the Duomo and Palazzo Ducale from the fortress

The most famous view of the Palazzo Ducale, towards the two towers of the façade, would be from the far right.

The 16th century city wall and outside of the fortress. When Francesco Maria della Rovere built new walls round the city, in 1507-1511, he included the fortress within them. It served as a convent in the 18th century, and is now part of the public park.

A slightly better view of the façade of the Ducal Palace

Back down the hill

Via Santa Margherita (near the museum of Raphael's birthplace)

-- It was about THIS big. A circuitous route back towards the car . . .

. . . and back to XX Settembre street in Gubbio.

The Squirrel pleased to see us back in the hotel

Dinner at Dulcis in Fundo on the Via Repubblica and Corso Garibaldi, very good (and not crowded)

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website