|

Dwight

Peck's lengthy tales Dwight

Peck's lengthy tales

Castle-Come-Down faith

and doubt in the time of Queen Elizabeth I

Part

1. ENGLAND (1577-1583) CHAPTER

IX. INTERROGATORIES FOR CHARLES ARUNDELL (1581) "Alone

in prison strong

I wait my destiny.

Woe worth this cruel hap that I

Should taste this misery!

Toll on, thou passing bell."

-- Anon. 1.

"Item to be demanded of Charles Arundell and Harry Howard. What combination

or secret pact was made at certain suppers, one in Fleet Street as I take it,

another at my lord of Northumberland’s, for they have often spoken hereof

and glanced at in their speeches." To

the first thus I answer, that I was never at supper in Fleet Street or at the

earl of Northumberland’s where any combination hath been made to any ill

purpose, and of this interrogatory I understand not the meaning. 2.

"Further for the same. If they never spoke or heard these speeches spoken,

that the king of Scots began now to put spurs on his heels, and as soon as the

matter of Monsieur were assured to be at an end, that then within six months we

should see the queen’s majesty to be the most troubled and discontented person

living." To

the second, as I never uttered, so never heard I of any such speech. This is as

void of truth as he is of honesty that so reports of me. 3.

"Further, the same. Hath said the duke of Guise, who was a rare and gallant

gentleman, should be the man to come into Scotland, who would britch her majesty

for all her wantonness, and it were good to let her take her humor for a while

for she had not long to play." To

the third, I do protest that I never used any speeches of the duke of Guise coming

into Scotland; it is a shameless lie and most maliciously devised.

|

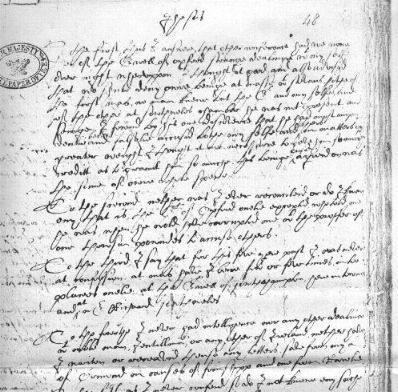

Charles

Arundell's replies to government interrogatories, 1581. Public Record Office,

State Papers 12/151/47. | 4.

"Whether Charles Arundell did not steal over into Ireland within these five

years without leave of her majesty, and whether that year he was reconciled or

not to the church likewise, or how long after?" To

the fourth, it is as true that I stole over into Ireland within this five years

as it is true I was reconciled the same years to the church of Rome, and if any

accuser can prove the first I will confess the latter to do him a pleasure. 5.

"Item. When he was in Cornwall at Sir John Arundell’s, what Jesuits

he met there and what company he carried with him of gentlemen."

To the fifth, I say that at my lying

in Cornwall, I saw just as many Jesuits as I have seen in her majesty’s chamber,

and that was never any. Other company I met in then with my brother, a quarry

of pleasure, to see our sister and accomplish business. 6.

"Item. Not long before this past Christmas, entering into speech of Monsieur,

he passed into great terms against him in so much he said there was neither personage,

religion, wit, nor constancy in him, and that for his part he had long since given

over that course of France and taken another way, which was to Spain: for he never

had good hope of the queen’s marriage since my Lord Chamberlain played the

cockscomb, as when he had his enemy so low as he might have trodden him quite

underfoot, that then he would of his own obstinacy bring all things to an equality.

And so he troubled him no more with the cause of marriage, and talked only of

the king of Spain’s greatness, piety, wealth, and how God prospered him in

all his actions, not doubting but to see him monarch of all the world."

To the sixth, I shall not need to use

many words to disavow this, these speeches have been too ordinary in Oxford’s

mouth, as my Lord Henry, Southwell, Raleigh, and as many as hath accompanied him

can witness. This springs from a muddy fountain. 7.

"Likewise both Charles and Henry. Likewise they have been great searchers

in her majesty’s wealth, having intelligence out of all her receipts from

her majesty’s courts in law, her customs, what subsidies of Parliament she

hath made since her coming to the crown, what helps by special gatherings made,

as for the building of St. Paul’s steeple, the lotteries, and other devices

from the clergy, and what forfeits by attainder or otherwise; and what pensions

were to some of her councillors, what gifts she had bestowed, what charges she

was at in her household, reparations of her houses and castles, fees, and a number

of things which now I cannot call to remembrance, and the charges she was at in

the wars of Leith, Newhaven, and other petty journeys in Ireland and Scotland

and in the time of the Rebellion of the Northern Earls, as well what she received

as what she spended in all offices and places." To

the seventh, of her majesty’s wealth I never made search or inquiry, and

of her receipts I never sought to understand. So ignorant of her majesty’s

receipts am I as I am not able to say what riseth out of her courts, her customs,

etc. The man who says so makes me pause to puke before answering further. 8.

"Likewise both Charles and Henry are privy, what increase hath been made

of souls to their church of Rome in every shire throughout the realm, who be of

theirs, and who be not, who be assured and who be inclined; and in every shire

throughout the realm, where they be strong and where they be weak; and this is

known by certain secret gatherings of money for the relief of them beyond the

seas, wherein there be notes of every household and the court, put into some other’s

hands of a foreign nation, a thing which if it be well looked into cannot be void

of great and notable practice." To

the eighth, which is a lunatic’s moonlit raving, as I cannot but wonder at

this fiction, so I was, it not my office, never registrar of the increase of the

souls that hath been made through the shires of England. Of any secret gathering

of money for beyond the seas, this shows as strange as the greater part of the

rest of these interrogatories, and for my own part, I hold them all as the ravings

of a lathering madman, piggish in his drink and slavish amongst men, and so I

commit him to the yeoman of his bottles, who has been no little causer of my persecution. My

lords, ever have I truly answered my examiners, and earnestly craved that we might

come to trial of this cause, but without any hearing of us or confronting of us

with this libelling monster, here we remain in durance, kept from all conversation

with our friends, while this gay courtier, borne out in this by my lord of Leicester,

goes grazing in the pastures and up and down the town, and as I am informed obtains

his release for the winter tournaments, for no cause but the bright figure he

must cut in the tiltyards, for so my lord of Leicester makes him never a man more

necessary for the holiday season. My

lords, I beseech you then, weigh my affliction, and so work as the world may behold

your integrity and upright dealing, to God’s glory and your own immortal

fame. I live in misery; stained in credit, cut off from the world, hated of some

that loved me, helped by none, and forsaken by all, for what just cause I know

not. My distress is great, my calling simple, and not able to avail anything without

the assistance of your goodness. Bring me to my answer; and, as you shall see

it fall out, my accusers can prove nothing against me. Vouchsafe me speedy remedy,

or at the least the justice of the law; and, if I have failed of my duty willingly,

let me feel the price of it. I crave no pardon, but humbly sue for favorable expedition,

for the which I appeal to your honorable judgments, and pray for good success

in all your desires. From Sutton, this 31 of January 1581, your lordships’

in all faithful devotion, Ch.

Arundell

C.A., in mine own hand.

A

Brief Answer to my lord of Oxford’s Slanderous Accusations 1.

Article. First he accuseth me of hearing mass six years past in Francis Southwell’s

chamber. Answer.

This article, being the only true thing he broacheth, is confessed; marry, but

protesting withal that whereas the statute law passeth on hearers of mass which

are not present at the queen’s service within the year, I have been coming

three whole months together; notwithstanding six years are now fully past since

the time was past which the law prescribeth. 2.

Article. It is further charged upon me for the further aggravating of the fault

that the priest which said this mass was a Jesuit, and that both I and the other

two were reconciled. Answer.

To this I answer, first, that reconciling in itself were not a felonious matter

until this new statute in Parliament which I find is passed but a little week

ago, and therefore misses me clean. And second, that it can avail them little

that the priest was of this now suspected order called Jesuits, unless they can

prove that I knowing him to be so notwithstanding heard his mass, for many plain

and simple men may light into suspicious company; again, the Jesuits were no more

offensive to the state seven years ago than any other priests, neither was there

any statute or proclamation then forbidding me them more than another. But the

truth is, to make short work, that this priest was neither Jesuit at that time

nor is any now, as Mr. Walsingham hath found by the flat confession of the seminary

priests within the Tower. 3.

Article. That my Lord Harry should be present when I presented a certain book

of pictures after the manner of a prophecy and by interpretation resembled a crowned

sun to the queen, etc. Answer.

Of all other this point is most childish, vain, and most ridiculous, for as my

Lord Harry never saw this painted book, I protest, much less expounded it or played

the paraphrase, so in my knowledge did he never hear of any such. And for his

further clearing in this cause, I will depose upon my oath he was never privy

to the book, and that Oxford showing it to me conjured me by solemn oath never

to impart a word of the thing to my Lord Harry because he would not hide it from

my Lord Treasurer. 4.

Article. That I should bring in a Jesuit to see the queen dance in her privy chamber.

Answer. Christ never receive me to his

mercy nor forgive me my sins if ever I spoke with Jesuit, much less brought them

to the sight of such an exercise, which had stood less with their severity to

follow than with my discretion to prefer. Condemnation

of the Accuser. Now I would require of charity and justice that these brief particulars

concerning him that chargeth me may be considered. 1)

That he was never kind to any friend nor thankful to any kinsman in general; 2)

That though he love no man living from his heart, yet of all he most detesteth

those that are either nearly kin by nature or have deeply bound him by their well

meaning; 3) That by devising

tales and lies he would set one man to kill another and hath sought my life by

a dozen practices and devices; 4)

That he would have set Hoby to have killed my Lord Harry; 5)

After he had once begun his accusation, he proffered me a thousand pound in money

in case I would concur with him in points whereof he had accused the Lord Harry

and Southwell, which I refusing and professing to die against him that would charge

me with the smallest thought against my prince, he would have given me as much

to fly, that by the flight of one he might have wreaked his deep malice on another.

But this succeeding as evil as the rest, with protesting that I should be torn

in pieces with the rack he left me, whereupon soon after one of us and within

two days all the rest were committed into ward. Now

the truth is that this null count, finding himself forsaken for his horrible enormities,

rather to be buried in the dung hill of forgetfulness than reported by any modest

tongue, obtained my lord of Leicester’s favor upon condition that he should

speed us three, and thus the bargain was concluded. My

lords, I have been reticent heretofore, and loath for modesty’s sake to fully

paint my adversary in all his horrible colors; but now my grief is such, shut

up with neither friend nor enemy to speak withal, whilst my detractor lives a

gay life pursuing all his former iniquinations, that justice requires me to mention

another matter otherwise better left in wraps. My lords, I must prove him a buggerer

of a boy that is his cook, as well by that I have been eyewitness to, as also

by his own confession to myself and others who will not lie. Moreover, Thomas

Power, weeping to my Lord Harry and myself at Hampton Court, confessed how my

lord had almost spoiled him, and he could not sit or stand for many days, and

yet he durst not open his grief to anyone. But

is this all, my lords? No, there is no end. He would often tell my Lord Harry,

myself, and Southwell that he had abused a mare; and said that the English men

were dolts and nitwits, for there was better sport in back doors, which they knew

not, than in all their occupying of women’s fronts, and that when women were

unsweet, fair young boys were in season, with so far worse than this as it irketh

me to remember, from all which strenuous living he hath as proof his yearly celebration

of the Neapolitan malady. Thus much for proof of his sodomy, who is a beast stained

with all impudicity. Next,

my lords, albeit (as I have said) reluctantly, must I truly hit him with his detestable

practices of hired murders, of which some hath been attempted, one executed, and

divers intended. And though it be long since, it may not be forgotten how Denny

attempted the killing of Nicholas Faunt, and shooting at him from a rest with

his caliver, struck his hat from off his head. And I would be as loath to omit

the killing of Sanckie (being sometimes a special favorite of this monster, but

discovered to be untrue) by his servant Weeks, who at the gallows confessed to

the minister that he was procured to this villainy by commandment of his master,

who gave him a hundred pounds in gold after the murder was committed to shift

him away, and so much was found about him when he was apprehended. But

leaving this, though it were not impertinent, I will go more near him, in my own

knowledge, for his intended murders against divers. At what time the quarrel fell

out between this monstrous villain and Mr. Sidney, he employs Raleigh and myself

to carry his challenge, but goes about instead to murder Mr. Sidney in his bed

at Greenwich. Let us neither forget his oath to kill Sir Henry Knyvet at the privy

chamber door for a speaking evil of him concerning a kinswoman of ours. Another

murder he intended against Mr. John Cheke, and would have put it in execution

if I had not told him I would betray him and so stayed him from this villainy.

And not long since, as my cousin Arthur Gorges well knows, Mr. Gorges had warning

given him to look to himself and how it was intended he should be slaughtered

on Richmond Green, going home to his lodging at twelve o’clock at night;

and another gentleman of Oxford’s revealed it to me, and this gentleman refusing

to be commanded by him to so foul a fact, was shaken off and for no other cause.

Lastly, if himself lie not, he hath practiced with a man of his own that now serves

in Ireland to kill Raleigh whenever he comes to any skirmish in the wars there,

and this he terms a brave vendetta; and of this intent I have advertised Mr. Raleigh,

as also of his lying wait for Raleigh’s life before his going into Ireland.

Lastly, my lords, having well

entered at last into this exposition of my lord’s virtues, I must conclude

him in his religion, which though said to be as ours is, is really of no man else’s.

To show that the world never brought forth such a monster, and for a parting blow

to give him his full payment, I must prove against him his most horrible and detestable

blasphemy in denial of the divinity of Christ, our savior, and terming the Trinity

as a fable. And that Joseph was a wittol and the Blessed Virgin a whore; my Lord

Harry, Raleigh, and myself were present when he spoke these words, and Mr. Harry

Noel will say that Raleigh told it him. To conclude, he is a beast in all respects,

and in him no virtue to be found and no vice wanting, which things for a time

have been dissembled, but long time may not be suffered. Do but consider, I pray

you, my lords, who is my accuser, and let these examples plead, and I will abide

your judgments with equanimity. Yours and her majesty’s ever to command,

From Sutton, this 8 of March 1581, C.

Arundell

To

my very good lord, Mr. Vice-Chamberlain, Sir Christopher Hatton, at the court,

give these. Right

honorable. As my well meaning hath always willed me, so doth necessity now enforce

me to write you these. My monstrous adversary (who would drink my blood rather

than wine as well as he loves it), as I am credibly informed, hath said in open

speech and in a manner of a vaunt since his coming out of trouble, that whereas

I built my only trust on the friendship of your honor, he had sped me to the purpose

by bringing me in condemnation of a printed libel that should be written against

you, whereunto a friend of mine being present, doubting whether I had written

this indeed, Oxford answered that he could not tell, but he was very sure that

he had given Charles his full payment by this discovery. Though

restrained for the present to conceal the authors for divers respects, when time

shall serve I shall willingly impart for your worship’s better satisfaction

all my knowledge. In the mean, I humbly crave this favor, that as the matter is

a mere supposal suggested by envy, vented by malice, and devised by others not

unlike himself common knaves, as shall appear, so you will suspend judgment till

truth shall deliver me from this improbable slander and lay it on him that best

deserves it. And if I thought

you were otherwise persuaded than I have deserved, I could not rest so well contented

in my present condition, which expected all help and succor from yourself, and

other friends I have not sought for my delivery, neither will I. Trial is all

that I require and trial shall acquit me, and hang the villain for sodomy that

hath no proof of anything but the slander of his own blasphemous tongue. Of this

last practice against myself, and others more monstrous, which shook the foundation

whereon I built all hope, I shall one day tell you more and make you wonder at

that which is come to light. In the meantime, I recommend myself, my cause, and

all to yourself, who can best judge of all. And here in durance I pray for the

queen and my good friends, of which number you are chief; and so wishing for that

opportunity wherein I may do you service, I commit you to that God that hitherto

protected me. From Sutton, this 15 of March, C.

Arundell

Arundell

sat by a thin flame far into the broad night, scribbling feverishly upon sheets

of paper spread before him on the table, piled carelessly by his stool. His face

showed the desperate concentration of one engaged in a duel with sabers, but he

had no saber, only a pen, to fight with.

| Go

back to the Preface and Table of Contents |  | Go

ahead to Chapter X. De Profundis Clamavi (1581) |

Please

do not reproduce this text in any form for commercial purposes. Historical references

for events recreated in this story can be found in D. C. Peck, Leicester's

Commonwealth: The Copy of a Letter Written by a Master of Art of Cambridge (1584)

and Related Documents (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1985). Feedback and

suggestions are welcome, Please

do not reproduce this text in any form for commercial purposes. Historical references

for events recreated in this story can be found in D. C. Peck, Leicester's

Commonwealth: The Copy of a Letter Written by a Master of Art of Cambridge (1584)

and Related Documents (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1985). Feedback and

suggestions are welcome,  .

Written 1973-1989, posted on this site 20 June 2001. .

Written 1973-1989, posted on this site 20 June 2001.

|